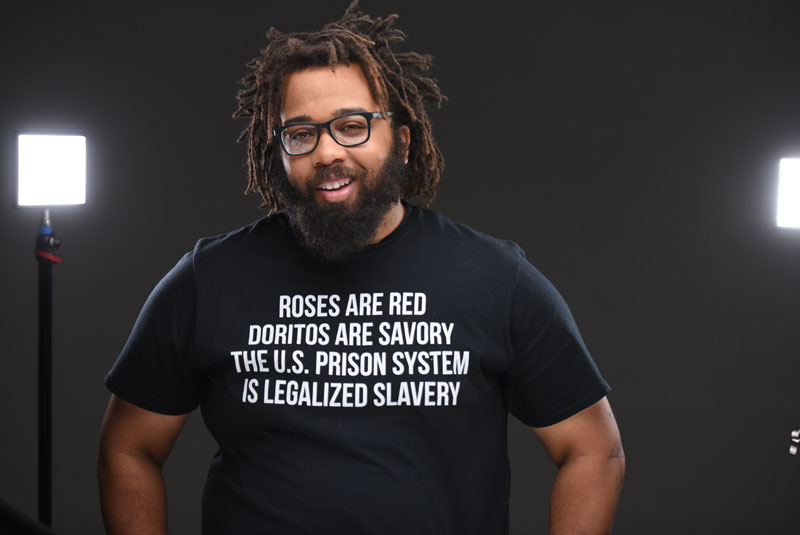

Philadelphia-based Kurt Evans is fighting for reform in the US criminal justice system – using food as his medium. Through the ground-breaking End Mass Incarceration dining series, a brave new restaurant business model and his community-focused activism, the Black American chef is driving change across the culinary landscape and far beyond. 50 Best profiles the first of its three Champions of Change award winners, presented in partnership with S.Pellegrino

“For me, it’s about getting different people to the table, that’s the only way to achieve inclusivity – and food is the driver, the thing that brings people together,” says Kurt Evans of the motivation behind his End Mass Incarceration [EMI] dinner series.

If you attend one of the Philadelphia chef-activist’s dining events, don’t expect a comfortable night: Evans wants you to be challenged, to meet people whose background and stories may be very different from your own. “If you buy two tickets, I’m going to split you up and then you’ll break bread with somebody you don’t know. You’ll hear the truth from individuals who have been formerly incarcerated. I’ve found that storytelling is very healing – you can hear someone’s story and you’re like ‘Wow, what can I do about this? How can I help?’”

So, let’s tell Evans’ story.

The 35-year-old African American was born and raised in the US city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. From an early age, he cooked with his grandmother, who had 10 children herself and was therefore, according to Evans, always cooking on a grand scale. “She cooked for her family, she cooked for church events, so she could never cook a small pot of anything, it was always for 20 or 30 people. Food has always been central in my life.”

Evans started the End Mass Incarceration dinner series in 2018 (image: Marc Williams)

Evans’ first job in food was flipping burgers at McDonald’s, but he already had a love for cooking and quickly developed ambitions to be a ‘real’ chef. He began staging and then moonlighting in better restaurants, working his way up the culinary ladder, moving from mass production to focusing on precision instead. Then, while working as an executive chef in a Southern-style restaurant in his home city, a desire to do something more than simply feed people was kickstarted by the relentless rise of social media.

“It came about through Instagram really. It gave me a platform and I realised I wanted to do more than just post food shots to get likes. I wanted to say to people ‘hey, while you’re here, take this information as well’.” And so Evans did just that: he used his nascent popularity to start campaigning on issues of racial justice and, in particular, the mass incarceration of Black Americans.

Criminal justice, race and food

Michelle Alexander’s seminal book, The New Jim Crow, which laid bare the deeply rooted and structural racism of the US criminal justice system, was a major influence on Evans, as was The Kalief Browder Story TV documentary series, charting one young New Yorker’s three-year imprisonment on Rikers Island without trial after not having enough money to make bail.

“I'm watching these documentaries, and I'm seeing these books come out and I’m asking myself how I can connect more people to this issue,” he says. “Other people are using their craft to make films or write books. I wanted to use my craft… to use food as the conduit to bring people together.”

Meet Evans in the video:

With Black Americans making up 20% of the overall population but accounting for more than 80% of the country’s prison population, the issue of mass incarceration is fundamental to the intersection of race and politics. Evans himself has had friends and family members who have been imprisoned: he has said that it was so common in his community that he actually thought he was meant to go to jail.

The End Mass Incarceration dinner series, which comprises more than 20 events to date, aims to address these issues by throwing different stakeholders together, from policymakers to former prisoners; campaigners to financial benefactors. In the process, each ticketed ‘family-style’ meal raises funds for a specific cause such as bail funds, expungement clinics [which work to help clear criminal records] or non-profit organisations such as Books Through Bars, which sends free books to those inside.

The original idea for EMI came directly from Black American culture, according to Evans, where food is frequently used as a means to solve problems. “In our culture, if you’re short on rent money then you have a party or a cook-out and charge people at the door. If you need funds because your kid’s going to college, you’ll have a fish fry… Food has always been an avenue for us to be able to raise money when it’s really needed.”

Slice of pizza, slice of equity

There is, however, plenty more to Evans’ food-meet-social-justice armoury – a cache of culinary weapons and initiatives that has prompted him to be named one of the three inaugural Champions of Change by 50 Best and its supporting partner, S.Pellegrino.

In 2019, as his EMI initiative began to gain traction, Evans was scouted to be culinary director of Drive Change, a non-profit organisation based in New York City. Drive Change seeks to help formerly incarcerated youths through professional experience in the culinary arts, training them to work in the hospitality sector and, in the process, providing greater agency over their lives. While the pandemic cut short Evans’ work there, it still had a profound impact on his outlook, prompting him to think holistically, and ultimately to raise his short- and long-term ambitions.

Champion of Change: Kurt Evans in a nutshell

Cause: Food insecurity and mass incarceration

Effect: Feeding those without access to fresh food; raising the issue of mass incarceration

Achievement: Getting policymakers and former prisoners to sit down together; setting up a new restaurant template

What’s next: Expanding the End Mass Incarceration dinner series; writing a book combining culinary culture with the civil rights movement

Final word: “My mission as a chef is to work with communities with compassion and implement programmess and systems that help combat food insecurity and mass incarceration. Food is something that gets people to the table – sharing your culture with someone, sharing your stories, that’s when it all comes together.”

After returning to Philadelphia, Evans opened Down North Pizza with a business partner in the city’s Strawberry Mansion district in March 2021, having raised funds by asking people to donate pizzas to those most in need over Thanksgiving. The already hugely popular pizza-and-wings joint exclusively employs formerly incarcerated individuals, while also providing career opportunities at a fair wage.

While Evans is not in the kitchen, he has been fundamental in creating a successful working example in Down North that he hopes can prove to be a template for other equitable, opportunity-providing businesses to follow – whether in Philadelphia, across the US or around the world. He would also like to adapt the model in the future to ensure all employees have a meaningful stake in such enterprises. “When I go into other business ventures, profit-sharing with people who’ve formerly been incarcerated will be the model. Economic freedom is the path to true freedom,” he says.

Down North serves ‘Detroit Style’ square pies, wings, salads, fries and shakes (image: Ted Nghiem)

At the root of the chef’s highly energized sense of purpose is his own experience, and that of his fellow African Americans. “I noticed that working in the restaurant industry – whether it was a fine dining restaurant or a mass catering type of place – the Chef was never Black. All the Chefs were white. I remember hearing [US chef-restaurateur] Marcus Samuelsson tell a story about working in a major restaurant overseas, but when he’d be coming out of the kitchen people though he was the dishwasher.”

Such far-from-rare incidents prompted Evans to research the historic marginalization of Black culture and, in particular, Black culinary culture. “A French chef can put a cassoulet on the menu, even though it’s traditionally ‘peasant food’, and charge a price for it. If a Black chef tries to sell you fried chicken, it’s not valued as highly,” he adds.

Somebody feed Philly

In 2020, chef Stephanie Nicole Willis (‘Chefanie’ to her friends) and four other chefs of colour, including Evans, co-founded Everybody Eats Philly, an organisation dedicated to fighting hunger, increasing food security and building community. “We believe access to healthy food is a basic human right and not a privilege. All people deserve regular nutritious meals,” she states.

Everybody Eats was born out of the pandemic: its original incarnation was a static operation called the People’s Kitchen (funded by José Andrés’ World Central Kitchen), feeding those most in need at the time. But following the widespread social unrest kickstarted by the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, Willis recognised that whole neighbourhoods of Philadelphia were increasingly food insecure – and she called on her fellow chefs to join her in combatting this burgeoning blight.

Everybody Eats Philly is accepting donations to further its mission (image: BeauMonde Originals)

“The grocery stores, corner stores, drugstores were completely decimated,” says Willis. “A lot of the people that live in these neighbourhoods don’t have access to vehicles to get to another neighbourhood to get groceries.” Everybody Eats Philly now distributes meals and fresh produce direct to these communities at events two or three times a month. Furthermore, the team embarked on a road trip to San Antonio, Texas, in February to feed those affected by the southern state’s unexpected winter storm, distributing thousands of their home city’s signature Philly cheesesteaks to cold and hungry residents.

Of her friend and co-founder, Willis says: “Kurt is definitely a leader. He’s very involved, especially in the Black community.” Asked what is behind his drive for change, Evans himself is modest: “I guess it’s just being in the hospitality industry – we’re like first responders. We have that type of mentality.”

EMI on the road

As a non-profit, Everybody Eats Philly is the fiscal sponsor of Evans’ EMI dinner series. With the substantial donation being made to Everybody Eats as part of the Champion of Change award in partnership with S.Pellegrino, the team plans to expand its initiatives: feeding and educating people – frequently at the same time. The funds will help buy a truck for Everybody Eats to distribute free fresh fruit and vegetables on a more frequent basis. It will also enable Evans to take his EMI series to different cities across the US including Houston, Miami and New Orleans.

“The problem of mass incarceration is common across the United States, but it looks different in different cities. Sometimes it is homelessness [that needs addressing most], sometimes recidivism, bail reform, parole violation… but a large part of the problem is lack of awareness. People are unaware of the pitfalls put in place for those that were formerly incarcerated, so education is the key.”

Evans speaking at an EMI dinner (image: BeauMonde Originals)

Speaking of education, Evans is also in the process of writing a book which charts the intersection between the civil rights movement and food. Platter Food will take in the formative role played by Georgia Gilmore, who fed the leaders of the civil rights movement in Montgomery, Alabama in the 1950s and 60s and raised funds through selling her sweet potato pie and fried chicken to aid the struggle. “Going from the [original] civil rights movement to the modern day, selling platters is something the Black community does. The book will tell the stories and recipes of people dealing platters out of their house, their church, their local community centre,” says the author. “Black heritage has not been respected, not valued, so I want to highlight it and bring some history to our food, too.”

Ultimately, Evans is optimistic about the future. He is politically active through the 215 People’s Alliance, a multi-racial collaborative fighting for equity and justice in Philadelphia. “I’m in a lot of spaces where people don’t look like me and I’m trying not to come off as an ‘angry Black man’. But I’m also finding that most people want to help, they want to know what they can do, and what we need from them. This [Champion of Change] award provides an even greater platform for more people to get involved.

“If we continue to help lawmakers, politicians and city officials to understand the phenomenon of mass incarceration, then I believe we will see change. Those people who have been formerly incarcerated need to have a hand in the policies and laws that are being written – to have their voice heard. They need to be centred in the process. That would be success.”

Champions of Change, presented in partnership with S.Pellegrino, recognises and celebrates three unsung heroes of the hospitality sector who have used the extraordinary events of the last 18 months as a springboard to drive meaningful action. It is part of The World’s 50 Best Restaurants 2021 awards programme and the evolving ‘50 Best for Recovery’ initiative.

To be the first to hear about the latest news and announcements, join the community on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.