In Part Two of 50 Best’s interview with Heston Blumenthal and the latest in our Best of the Best-focused Visions of Recovery series, supported by S.Pellegrino, the celebrated chef who took The Fat Duck to No.1 in The World’s 50 Best Restaurants 2005 gives an enlightening introduction to his current projects. He provides unique access to the world he operates in today – at the vanguard of physiological science and approached with the same abstract attitude that made his name in the kitchen. Pull up an impartial, open-minded seat and enjoy the journey into the mind of a genius

Heston Blumenthal is subjecting rice to emotions.

This morning, he structured the water that would become his almond milk with a singing bowl. Later, he will train positive thoughts on the water in his glass to improve its efficacy.

For this section of 50 Best’s conversation with Blumenthal (see Part One here), we venture outside the realm of restaurants and step into the future of food, drink and how the mindful act of eating can influence our own happiness and, indeed, health.

To follow a dialogue with Blumenthal requires us to venture away from the considerations of conventional understanding. It would help to imagine yourself in the room with Blumenthal when he first started talking about using liquid nitrogen to make ice cream, or employing a laboratory water bath to maximise the flavour of salmon almost 30 years ago. At the time, many scoffed. Today, the techniques he pioneered are commonplace in kitchens all over the world.

The next stage of Blumenthal’s career looks to the greatest unknown: ourselves. “I’ve become increasingly interested in the hero’s journey,” says Blumenthal, 54. “Everyone is a hero; everyone is in it on their own. It’s why we connect so well with Star Wars, Harry Potter and superhero films. We all go through pain, pleasure and suffering. Our own body and our own internal thoughts and feelings are the most complex things on the planet.

“For the past 25 years I’ve amassed a whole lot of information and made a bunch of discoveries. I’m trying to take a journey to the centre of my own Earth and then look out again with me as a walking, talking experiment. It starts with becoming more mindful in day-to-day processes and minimising distractions, but also being able to recognise what is happening in my own body. It is giving rise to varied discoveries and I’m actually more excited about this than I ever have been about anything.”

Taking time to focus on fledgling areas of physiological science has replaced designing ground-breaking restaurant dishes for the trailblazing chef. At his new home in the south of France, he spent six months building a sprawling kitchen-cum-laboratory, where he is based today with his colleague Dimitri Bellos, previously Restaurant Manager at The Fat Duck. The findings they make in France are digested and transported back to the restaurant in Bray, southeast England, which was named The World’s Best Restaurant in 2005.

Blumenthal and The Fat Duck team in the early years

Between them, they spend as much time discussing philosophy and advanced scientific theory as they do creating an environment ripe for culinary discovery. “The modern world worships quantity – that is our God,” he begins. “We want more money, we want more success, we want to live longer, we want more friends on social media. It’s all quantity, quantity, quantity and there’s nothing wrong with that, but if it is at the expense of the relationship with ourselves, that’s where the problems start. I read a book by an Irish palliative care nurse working in Australia about the regrets of the dying. The single biggest regret people reported on their deathbed was that they wished they had spent a life being true to themselves. The relationship we have with ourselves is so precious: it’s the hero’s journey.”

The mindful sandwich

According to Blumenthal, for most of us this can begin with a more mindful approach to eating. “The thought of meditation scares a lot of people off because you need to learn and practice it. People who play piano, take up a sport, practice yoga or go to the gym; you have to learn the actions before you can appreciate the results,” postures Blumenthal. “That can be a lot of work for some. Either they don’t have the time, or it’s not how they want to spend their time. However, we can’t get away from the fact that we have to eat – the discipline and learning is already there.

“So this gives us a wonderful platform to begin to eat mindfully – think of it as a mindful sandwich, if you will. Imagine you’re typing into your computer, busy working, and you’ve got your sandwich packet in your bag and you think you’re too busy to take a lunch break. But now think that you can work extra hard for the next hour to earn yourself 15 minutes to go to the park to eat the sandwich. Take 30 seconds to imagine the feeling of the park bench you are sitting on, with your feet on the floor. Think about the touch and noise of the sandwich packet; the crunch of the cellophane. Maybe it’s raining and you can hear the droplets on the umbrella; maybe you can hear the birds in the trees. In essence, you’re setting yourself a doable ambition. It’s not climbing Everest, it’s achievable in a short space of time and you’ve done your work so you’re not feeling guilty – you’ve already achieved something and your reward hormones start to flow.

“Now, you walk to the park and actually eat that sandwich mindfully. Focus on how it feels to touch, the smell, how it feels on your top and bottom lip, read the ingredients on the packet and so on. When you eat this sandwich, I promise you will feel such a greater level of fulfilment from the sandwich when you get back to work.”

It’s in setting these simple, achievable goals that – according to Blumenthal – is at the core of maximising our own life experience. These, in turn, create the pathway to greater personal discovery and Blumenthal is exploring the reasons why and how we are more sated by this mindful sandwich.

The answer, he says, is the connection between our gut and brain. “Our sensory organs are the gatekeepers for the gut,” he continues. “The gut and the brain have a complete endosymbiotic relationship through the spinal column, connected by the vagus nerve [endosymbiosis refers to a state where one organism lives inside another and where the two operate as a single organism]. What we eat affects our microbiome [the trillions of bacteria, viruses and fungi that make up the gut environment] and our mood affects the microbiome, too. In the gut we have around 200 trillion microbes – more than there are stars in the universe – and these are refreshed every 72 hours. There are also proven links between Alzheimer’s and the microbiome balance, too.

“We use phrases like ‘I’ve got a gut feeling’, ‘I know in the pit of my stomach’ and similar metaphors all the time. We’re actually onto something here – our gut senses things before the rest of the body and the more attention we pay to this and look to influence the environment positively, the healthier and happier we can be.”

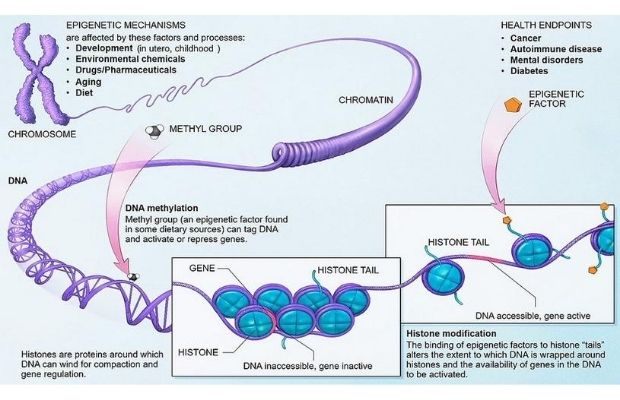

Academic research from the past decade corroborates this and takes us further along the path of how our surroundings affect our day-to-day state. Leading biologists such as Dr Bruce Lipton, Dr Candace Pert and Dr Joe Dispenza are pushing forward in the field of epigenetics, which is essentially discourse around our ability to control our own genetic destiny by influencing the factors that have control of in our environment.

Though it is not without controversy. To buy into epigenetics requires us to disregard a lot of the conventional understanding linked to DNA and the way in which it defines how we grow, develop and behave. Epigenetics proposes that if you give a cellular organism the correct environment to thrive, it can alter its genetic code to become a more successful version of itself.

A basic overview of epigenetics

“Our microbiome diversity and activity has a massive impact on our emotions,” says Blumenthal. “We can tell ourselves these little white lies, which can be hugely influential. What we think what we feel has a massive effect on the relationship with the food that we consume. If you drink water thinking ‘if I don’t do this I’m going to die’, that water doesn’t become anywhere near as beneficial. By enacting a positive thought process as you drink, it will be received more efficiently by the body. Take my three-year-old daughter, for example. The way she gulps and slurps water is just magical and it’s this kind of appreciation that the body welcomes.

“I know this sounds a bit spiritual and philosophical, but there is a biological, physical argument to back this up: the more connected we feel and the more in the moment we are with the food or drink that we’re consuming, the more positive that endosymbiotic relationship becomes. We used to think that you ate solid foods, it went into the digestive system and that was it, but there's an emotional side to the gut. There are brain cells in the gut and in five or 10 years’ time, I believe the whole thing is going to change… I can feel it in my waters.”

For Blumenthal, this process chimes loudly with the situation we find ourselves in the hospitality sector today. “I think restaurants coming off the back of Covid and with the dialogue around global food shortages, it marks the perfect time to eat with more gratitude and have a better connection with what we consume. By valuing more mouthfuls of food, we essentially expand time – there is a big difference between feeling full and feeling fulfilled.”

The business of emotion management

The positive thought process Blumenthal encourages us to adopt in eating extends far beyond food and drink. We move onto the topic of his biggest fears across the course of his career and the actions he engages to overcome them. “I was a people pleaser,” he admits. “My greatest terror was that I would be disliked. I don’t have a fear of life, but do I have a love of it today? Yes, I guess I do. Everything goes up and down and I cherish some memories more than others.

“We have the freedom to choose how we react emotionally to a given situation. There’s a great book called The Courage To Be Disliked [Ichiro Kishimi] where the author talks about Mortimer Adler, a philosopher in the late 1800s, who had a theory called ‘separation of tasks’. Basically, if you think somebody doesn’t like you, it is not your task to try and do anything about it. Your only task, if you are not comfortable with that emotion, is to separate the tasks. The person may actually like you, but if you feel as though they don’t, then it’s your task to do something about your own feelings. I love one of the quotes in there: ‘The biggest freedom we have is the freedom to choose how we emotionally feel.’ However, it's also possibly the most difficult thing to do in the world.” The hero's journey is never without tribulation, after all.

Emotions are powerful things in Blumenthal and his contemporaries’ view of the world. He believes, and is on the way to proving, that they have an impact that we are only just beginning to understand. “The late professor Masaru Emoto did a lot of experiments on subjecting water to emotions: some thought, some spoken, some written,” he explains. “I went to the World Water Congress last year and Emoto’s assistant made a presentation and explained their experiment. They made 50 samples and gave either negative or positive emotions to the water and then showed the ice crystals they created, when frozen to -23C. It really was incredible. There were a couple of Nobel Prize winners at this congress and they were all talking about the structure of water and its ability to carry emotion, because emotions are vibrations which carry data that has a memory. In the next five years, this area of research is going to explode.”

View this post on Instagram

“Professor Masaru conducted another experiment with three jars of rice and water and every day, he wrote words such as ‘love’ and ‘gratitude’ on one, wrote ‘hate’ on another and the third, he completely ignored. The jar that had abusive intent started to go black and the one that was ignored went rotten. The one with positive emotions attached, the water turned gold. As our bodies are 70% water, you can imagine what negative emotions are doing inside ourselves.

“If somebody sulks in a room, it's infectious. Or in a kitchen, or front of house, for example, in the restaurant you can feel that stress. It’s a virus, an emotional virus. On the flipside, if someone is really happy they can share that positive energy with the room and everyone is aware of it.”

Blumenthal stops and announces he has been conducting similar experiments at home. He picks up his laptop, walks into another room and trains the camera on three jars of rice above his fireplace. “Dimitri has done eight of these experiments now and written the emotive words in English and in Greek – we’ve had the same results, similar to Professor Masaru, every single time.”

“On the positive one, it had that golden smell of a fresh, ripe, washed-rind cheese, but with a floral sweetness to it. The one that had been given the abuse had the smell of an old, stuffy, poor-quality cheese and the one that was ignored with indifference had a smell like human excrement, with vinegar.” Blumenthal’s chef’s nose clearly hasn’t deserted him.

Making water sing

Blumenthal is also experimenting in structuring water with Tibetan singing bowls. These are deep, thin-walled vessels generally made from crystal or brass. They are filled with water and either played like bells, or with a wooden instrument that is passed over the rim of the bowl to produce a resonant sound that is transferred to its liquid contents, causing it to vibrate.

A traditional Tibetan singing bowl

Buddhists have long revered the healing capabilities of water charged in singing bowls and Blumenthal is empirically assessing its efficacy. He is also planning to roll it out in his restaurants. “We’ve done all sorts of experiments and blind tastings across my property,” he explains. “We’ve made ice cream with milk subjected to singing bowls and you can taste the difference. We might well be making stocks with powdered crickets and insects, but working with water that has gone through these vibrations is where the real future lies. There are seven main singing bowls and they’re made from seven different materials and generally produce a different result.

“This morning, I had a smoothie made with almond milk with structured water. Last week, we reopened The Fat Duck and one of the things I did for the relaunch was to send my voice recording of positive emotion. We put it through a cymascope [a machine which reports a pattern of aural vibration] and we plan to put this cymaglyph image onto the bottles of water that we will serve in the restaurant in a see-through sticker, which kind of ties into the rice experiments.”

Blumenthal may not have worked the pass for a number of years, but it’s without question that his desire to explore new frontiers of food science has not waned. His current work, while outré to some, is at the very extremity of conventional understanding. He is looking to push the same boundaries that he did 25 years ago when he opened The Fat Duck and brought about some of the biggest changes in how we view food in recent history. It might take tangential thought to comprehend it, but if history is anything to go by, there’s a good chance that the gastronomic world will soon fall into his slipstream.

Blumenthal pictured recently in France

“We live in our heads,” he concludes. “We live in the things, the objects and people around us. We want to go to Mars. We want to conquer Everest and we want to run marathons, which is amazing. But we don’t want to put our wellies and hard hats on and look inside. It’s a scary place, but it is our future. With all the things that are changing in today’s world, it is the perfect opportunity to be in the present.”

Stay tuned to 50 Best Stories for the next instalment of Visions of Recovery series. Visit the Restaurant Recovery Hub and the Bar Recovery Hub to explore useful resources and read the stories of chefs and bartenders around the world. Follow 50 Best on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to discover the latest news and features in the hospitality industry.

Photography by: John Scott Blackwell (@th3photographer); Pixabay